In 1296, following Edward I’s conquest of Scotland, the Yorkshire Chronicler, Langtoft, wrote: “Now the islands are all joined together, and Albany reunited to the kingships, of which King Edward is proclaimed lord. Cornwall and Wales are in his domain, and great Ireland at his will. There is no king, nor any prince, in all these countries Save King Edward, who has united them thus. Arthur never held these fiefs so fully!”

While Edward I was recognised by contemporary writers for such an accomplishment, the question of whether Edward I personally harboured such a vision for Britain is up for discussion. Did Edward I envision himself as a new King Arthur, the only other monarch to unify Britain under his leadership, and can his actions and policies towards Wales and Scotland be underlined by an ambition to unite Britain?

To answer this question, it is crucial to define what Britain meant in a mediaeval context. The understanding of Britain as the island to which Wales, Scotland and England belonged was commonplace; Britannia and Albion had long been established names for the island. The concept of Britain was most notable within Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae. Completed around 1139 AD, Geoffrey claimed his work was derived from an ancient book in the British language that told, in an orderly fashion, the deeds of all the Kings of Britain spanning a two-thousand-year period. His work not only served as the sine qua non to King Arthur but propagated the idea that all Britons share a bona fide Trojan ancestry. The English swiftly embraced Geoffrey’s account, and a concept of a British past of the greatest antiquity became the historical cornerstone of a national identity. Geoffrey thus did more than anything to make men conscious of the term Britain.

By the late 10th century, England and Britain had became synonymous, with England being regarded as a more up-to-date name for Britain. Henry of Huntingdon referred to Britain in his Historia Anglorum as “the most celebrated of islands, formerly called Albion, later Britain, and now England.” Writing in the 1180s, Walter Map referred to Henry I as ‘King of England… Lord of Scotland, Galloway, and the whole English island.’ Gerald of Wales also praised Henry II for ‘including by his powerful hand in one monarchy the whole island of Britain.’ It was thus clear that contemporary writers not only understood the concept of Britain but regarded the English as the rightful inheritors of the island.

There is evidence that Edward I was well acquitted with an understanding of the British past, particularly in relation to Geoffrey's Historia Regum Britanniae. For example when Scotland appealed to the Court of Rome against the injustices inflicted upon them by England, Edward commanded his secretaries to collect materials to substantiate his right over Scotland, and a letter, addressed to Pope Boniface VIII, was drawn up in 1301. In this letter Edward writes: “The kings of England, by the right of lordship and dominion, possessed, from the most ancient times, the suzerainty of the realm of Scotland… and they received from the self-same kings…homage and oaths of fealty.” Edward invokes the founding stories of Britain from Monmouth’s work relating to how: “Brutus landed… upon a certain island called at that time, Albion… He called it, after his own name, Britain, and his people Britons… He gave to his first born, Locrine, that part of Britain now called England… with royal dignity being reserved for the eldest.”

The source goes on to provide a list of various examples of English overlordship in Scotland, including that of Edward the Elder, Æthelstan, and Canute. Thus, illustrating that Edward was assuming a role to unite Britain under his rule, akin to Æthelstan and the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. The letter stands as the most compelling piece of evidence explaining Edward I’s justifications for his claim to overlordship in relation to the Great Cause. Edward firmly believed that “the Scots were subject to the realm of England” by antiquity. The letter also refers to King Arthur, whom Edward describes as being: “King of the Britons, a prince most renowned, subjected to himself a rebellious Scotland…and afterwards installed as king of Scotland Angus…and in succession all the kings of Scotland have been subject to all the kings of Britain.”

This reference is crucial, as King Arthur was not only renowned in Britain, but across Europe too. The fact that Arthur installed a subject king in Scotland gives immense credit to Edward’s claim of overlordship. Geoffrey of Monmouth describes King Arthur as being imperial and dominant, that he “had a claim by rightful inheritance to the kingship of the whole of Britain.” What is outstanding, is that this is not the only instance where Edward I had made symbolic references to himself and the legendary king.

In fact, Edward was a great enthusiast of an Arthurian past. During Edward’s time in Sicily, Retichello of Pisa borrowed a book of Arthurian romances from him, which served as the basis for his work Meliadus. The epilogue of this work implies that it was written at Edward’s express command, and there is no other evidence of literary patronage by Edward outside of this incident. Additionally, Edward’s wife Eleanor, is also documented as possessing a library of the Arthurian type, with Girard of Amiens dedicating one of his Arthurian works to her. Eleanor’s interest in the Arthurian legends may have likely been a significant influence on Edward himself. It was clear that Edward exhibited a strong concern with both the historical and the romantic traditions of King Arthur.

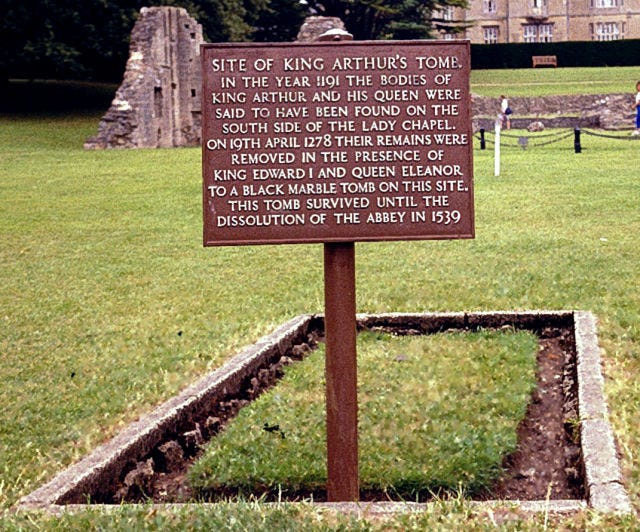

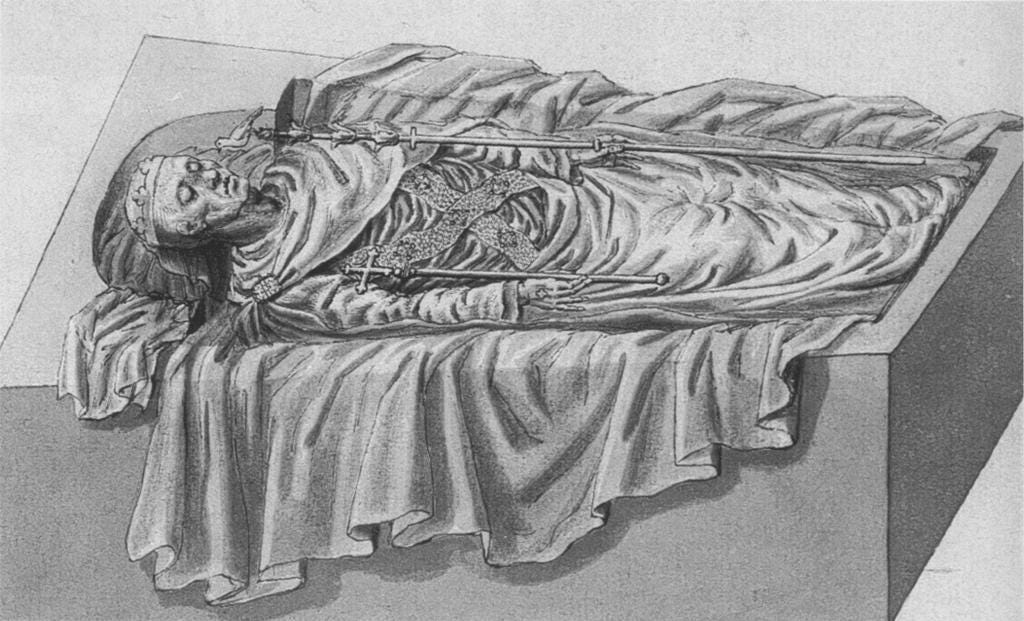

After achieving a decisive victory against Llwelyn ap Gruffudd during the Easter of 1278, King Edward and Queen Eleanor visited Glastonbury Abbey to reinter the remains of King Arthur and Queen Guinevere in a ceremony reminiscent of the translation of a saint’s body. Gerald of Wales records that the burial of the lost king had originally been discovered in the 12th century, by the monks of Glastonbury, after Henry II “disclosed to the monks some evidence from his own books of where the body was to be found.” Thus after his Great-Grandfather, Edward was the first king to take an active interest in the grave, as Henry II died before the excavation of the abbey could be completed. Every effort was made to ensure the event was memorable. Edward personally wrapped Arthur’s bones in silk, while Eleanor similarly prepared the remains of Guinevere for reburial. The disinterment of the bodies too occurred at twilight, a time believed to heighten ceremonial power due to the representation of light and dark. The choice of Easter for the ceremony not only drew in large crowds, but also symbolised a time of change from the normal order, in this case the end of a reign and succession of a new monarch. Edward thus came to Glastonbury not to praise Arthur, but to bury him. The burial undoubtedly aimed to connect the English monarchy with King Arthur, signifying English strength while also emphasising that Arthur would not be coming back to save the Welsh; a prevalent prophecy at times. The burial of King Arthur thus stands as the most compelling evidence of Edward using the legendary king as part of a British vision.

However this was not the only instance where Edward made use of British antiquity within Wales. Following the death of Llwelyn, Edward initiated the construction of Caernarfon Castle in 1283. It stood as an example of the many crusader-style castles Edward had built in locations significant to old British legends. Edward had instructed his architect, James of St. George, to model the castle on the legends of Magnus Maximus, who had dreamt of a beautiful maiden dwelling in a great castle, with towers echoing the walls of the city of Constantinople, by the mouth of a river flowing into the sea. What was remarkable about this, is like the burial of Arthur, the body of Magnus Maximus was found in Caernarfon and reburied on Edward’s orders. Thus illustrating that Edward knew how to appeal to a British past and comprehend the traditions of his land.

Similarly, after Edward I annexed the principality of Wales to the English throne in 1283, he received as a token of submission the legendary crown of King Arthur. As an Waverly annalist adds “the glory of the Welsh was thus transferred to the English.” This act symbolised Edward’s supreme authority over Wales. Edward’s confiscation of the Stone of Scone from Scotland and the crown of John Balliol also carried a similar significance. The naming of Edward’s son as ‘Prince of Wales’ too was important, as it sent a clear message to the Welsh that their old order was gone, and that England had come to replace their throne. Both events thus symbolised that Edward believed that England had supreme authority in the isles. That it was England that granted autonomy to the kingdoms, and it was England’s to take it away in accordance with historical tradition.

In 1284, Edward commemorated the conquest of Wales by hosting a roundtable event at Nefyn, strategically chosen to emphasise the extent of his victory, given the area’s associations with the prophecies of Merlin. The event was orchestrated in the same Arthurian vein as Arthur’s burial and the possession of Arthur’s crown. What is outstanding about this, is another roundtable event occurred in 1302 at Falkirk in Scotland, following the smashing of the Scots. The event also marked the great victory over William Wallace at the same place four years before. These events were most certainly political tools employed by Edward to show his newfound authority as the overlord of Britain. Additionally, they may also indicate that Edward likened himself to the legendary status of King Arthur. For example, outside of Wales and Scotland, he commissioned the construction of a round table, still displayed in the Great Hall at Winchester. Thus, it was clear that Edward actively pursued and celebrated the vision of a Britain under his jurisdiction.

Writers of Edward at the time regarded his British vision as one of his remarkable achievements. A lament following Edward’s death, written by a local author, presented Edward I as: “Entirely without equal, outshining not only Arthur and Alexander but also Brutus, Solomon, and Richard the Lionheart…We should perceive him to surpass all the kings of the earth who came before him. “ Langtoft also depicted Edward in Arthurian terms, suggesting his might exceeded Arthur’s as he had effectively united Britain. With contemporary writers celebrating Edward’s accomplishment of uniting Britain, it is likely that Edward thus harboured such a vision himself. This is evident not only in his interest and display of the Arthurian legends, but within his letter he sent to Rome justifying his actions in Scotland.

Edward I undeniabl held a British vision and often likened himself to King Arthur, given his interest and display of the Arthurian legends. Whenever Edward I had originally meant to bring Wales and Scotland under his control may never be answered. However, a British vision for Edward had come into fruition after the fact. Edward knew how to appeal to a British past and comprehend to his own rule the traditions of his land. It is among one of the reasons Edward had managed to restore to power a shattered country his father had bequeathed him. During Edward I’s coronation, he removed his crown and vowed to never wear it again until he had reclaimed the lands his father had lost. But by the end of his life, Edward had achieved a mightier feat. He instead restored that which King Arthur had built in his lifetime: a unified Britain.

Primary Sources:

- Henry Of Huntingdon and trans. Greenway, D. The history of the English people, 1000-1154. (New York: Oxford University Press. 2002)

-Geoffrey of Monmouth and trans Thorpe. L. The History of the Kings of Britain. (Penguin UK, 2015)

-Langtoft and trans. Wright, T. The Chronicle of Pierre de Langtoft, in French Verse, from the Earliest Period to the Death of King Edward I. (Longmans, 1866)

- Stones, E.L.G. Anglo-Scottish Relations, 1174-1328; Some Selected Documents. (Thomas Nelson, 1965)

- Walter Map and trans. M.R. James. De nugis curialium: Courtiers’ Trifles (Oxford, 1983)

Secondary Sources:

- Ashe, G. The Quest for Arthur’s Britain. (London: Paladin, 1972)

-Broun, D. Scottish Independence, and the Idea of Britain. (Edinburgh University Press. 2013)

-Davies, R.R. The First English Empire: Power and Identities in the British Isles 1093-1343. (Oxford University Press, 2005)

-Hay, D. The Use of the Term ‘Great Britain’ in the Middle Ages. (Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 89, 1958)

-Loomis, R. S. Edward I: Arthurian Enthusiast. (B. Franklin, 1953)

- MacColl, A. The Meaning of ‘Britain’ in Medieval and Early Modern England. (Journal of British Studies, 2006)

-Morris, Marc. A Great and Terrible King: Edward I and the Forging of Britain. (Pegasus Books, 2016)

-Prestwich, M. Edward I. (Yale University Press, 1997)

- Powicke. F.M., King Henry III and the Lord Edward, vol. 2 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1947)

- Sanford R.M "Edward I and the Appropriation of Arthurian Legend" (Western Kentucky University, 2009).

- Taylor. A. The Welsh castles of Edward I. (London Hambledon, 1986)

Bravo! Well written piece.

Wow! I was totally ignorant of this part of country’s history. There’s much to think on. Thank you Elizabeth 😃